Work Text:

They Wanted A Son

That evening, Hilda was excited. School had been long and boring, filled with subjects she knew she would never need, but the flat was warm and cozy, filled with the smells of home. Her mum had brought back a new board game; she’d just seen it while she was out, apparently, and thought it looked fun, so now they were getting ready for a family game night to try it out.

So Hilda had taken up her position on the sofa; Twig was curled up beside her, his tail encircling his little half-asleep body, while Johanna sat comfortably on her other side, a familiar warm smile on her face.

Alfur stood on the table in front of her, his gaze buried in one of the game’s rulebooks, sprawled out at his feet. There were three books in total in the box, but two had ‘Do Not Read’ printed across the front in an ominous font, so he’d had to settle for flipping through the third.

“So, Alfur,” Johanna broke the comfortable silence, affection in her voice, “what do you think?”

“This is very comprehensive,” he hummed approvingly; Hilda couldn’t suppress a quiet giggle at that. He looked up, waving an arm over at the other two books. “It says we’re not supposed to open the others until the haunt phase starts.”

“Huh,” Hilda noted, shifting forwards to get a better look. “Sounds like you’ve got your work cut out for you.”

The elf’s reply was cut off by a familiar sound, a quiet, ethereal tinkling from down by the far wall. Hilda turned just in time to see a burst of pink light where the skirting board met the floor, and in a flash the familiar shape of Tontu popped out into the room. Except it wasn’t just him; a large cardboard box loomed in his arms, almost as tall as he was, and he wobbled under the weight as he stumbled forwards.

“Tontu?” Hilda asked quickly, watching as the nisse plonked it down on the table with a quiet grunt of exertion; Alfur jumped at the impact. “What’s that?”

“Yours, I think,” he replied dryly, dusting down his hands. Hilda eyed it with interest; her mum shifted closer, perching on the edge of her cushion, and opened the dusty flaps. Her eyes widened as she took in the sight below.

“Is this…?” She trailed off, lifting a large flashlight out of the box. “It’s our old camping stuff!” She set it aside, digging back into the hoard with a wry smile on her face. “I thought all of this got lost in the move; looks like it wasn’t so lost after all.”

Tontu nodded in agreement. “I was looking through your old nisse’s stuff when I found it,” he explained, giving a little shrug under his sweater. “I guess they took it.”

Hilda peered over, the board game forgotten, replaced by new interest. Sure enough, under the lid was a jumble of familiar items; sleeping bags, the old tent groundsheet, another flashlight, and more besides. But what really got her attention was a flash of faded yellow, sticking out at one corner of the battered cardboard.

She reached over, her fingers finding soft wool, and tugged hard. For a moment the fabric held fast; she pulled again, and suddenly everything shifted at once, tent spikes and tangled clothes thrown out of the way with a clatter. Triumphant, she held up her prize; a yellow sweater, the same shade as the scarf that fell down her front.

“I thought I’d never see this again,” she noted happily, memories of the move rising up in her mind as she looked the old thing over. Without looking up, she added, “remember when I first lost it, and I had to wear my old brown one to Sparrow Scouts?”

There was no reply; Hilda glanced over, only to feel a sudden surge of worry at the sight of her mum. Because Johanna wasn’t smiling anymore; all of the warmth and curiosity was gone from her expression, replaced by something uncomfortably hesitant. She was peering down into the hole Hilda had made in the box’s contents, her mouth just slightly open and her eyes down.

“That can’t be…” she muttered, her voice a whisper in the empty air. Gingerly she reached down, her hands disappearing into the box, and carefully she pulled another shape from the pile inside. To Hilda it looked like a shoebox, made of threadbare maroon cardboard, and her mum let out a shaky breath as she held it up to the light. “I was sure I’d lost this.”

“Mum?” Hilda couldn’t keep the worry from her voice, but her mother didn’t seem to notice. She just held the box close, one hand gingerly lifting the lid; it was as if all she could see was the thing in her hands.

Alfur noticed too; he scurried across the game box and down onto the table, over to where she was sitting, and waved one tiny arm. “Umm, Johanna?”

Johanna was still in her own world. Her breath hitched as she opened the box, cracking the lid just enough to see inside. Hilda craned her neck, her stomach squirming with confusion and concern, but she still couldn’t see what had her mum so upset. So she scooted over, leaning in close, and gently put one hand on Johanna’s arm.

Her mum jolted at the touch, tension rippling up through her whole body and her shoulders jerking back. She blinked, her gaze snapping up and darting around the room before it fell on the child at her side.

“Oh,” she said quickly, letting out another shaky breath. She shook her head, as if trying to clear whatever had over taken her mind, “sorry, sweetheart.” Something lingered in her gaze, the warmth still missing, and Hilda couldn’t ignore her growing concerns.

“Are you okay?” she asked gingerly; her mum’s eyes widened just a little, and she shifted uncomfortably.

“You did kinda zone out there,” Tontu added; he’d moved in closer, and though she couldn’t see his face, Hilda was sure there was a hint of worry in his dry words. Johanna looked down, gently closing the box and setting it carefully on the table.

“I’m fine,” she tried to deflect, but her voice was still shaken. “I was just surprised to see that old thing, that’s all.”

Hilda’s narrowed her eyes, unconvinced. “What is it?” she asked, glancing between the box and her mum’s face. The discomfort in the woman’s eyes only grew at that.

“It’s nothing,” she said too-quickly, her expression suddenly hardening. “It’s just some stuff from the old house,” she insisted, something strained creeping into her voice, “nothing you need to worry about.” Hilda frowned at that, something squirming uncomfortably inside.

She felt curiosity growing in her gut, mixing with the concern she already had for her mum. Restlessness rose as a result; she was sure now that she had to see what was in there, what had affected Johanna so badly; her feelings wouldn’t be sated until she did. So she scooted forwards again, half-reaching out towards the box.

“Can I see, then?” she asked awkwardly. Her mum let out a sigh, what might have been frustration growing in her expression.

“No, Hilda,” she said firmly, her brow furrowing, “you can’t, okay?” Her words were clipped, trying to pre-empt any argument, but Hilda couldn’t stop herself from talking back. Before she could really think, more words spilled from her throat, her own concern turning to anger.

“Why not?” she demanded, throwing her arms wide. “If it’s nothing, then-”

“Because I said so!”

It wasn’t a shout, but Hilda still flinched at the harshness in her mum’s tone. For a moment she was silent; all of her curiosity withered inside, swallowed by a sudden wave of cold guilt that made her squirm uncomfortably. All she could think was that she’d hurt her mum, that she should have just let Johanna keep her boundaries, and that thought was like ice in her gut.

“I’m sorry, Mum,” she said quietly, looking down, unable to bring herself to meet Johanna’s gaze.

“Oh, Hilda,” her mum sighed, the anger gone from her voice. Hilda felt one arm reach around her, pulling her gently into a half-embrace at the woman’s side; she looked up in surprise, only to meet eyes full of regret.

Johanna went on softly, giving Hilda a reassuring squeeze. “I’m sorry too,” she admitted, glancing away and then back to her daughter. “I didn’t mean to snap at you, I just…” another sigh escaped her lips, swallowing her explanation for a moment. “I don’t like thinking about what’s in that box; it’s old, personal stuff, and I never wanted you to have to worry about it.”

“But I am worried,” Hilda protested softly, pressing one hand to her chest, “because you’re upset. I just… I worry about you too sometimes, Mum, and I got caught up in that.” Johanna’s expression softened at that, a tiny half-smile crossing her face.

“I think Hilda speaks for all of us,” Alfur’s voice added, concern of his own in his tiny words. Johanna looked over, meeting his gaze as he stepped over to the box. “Your privacy is up to you, of course, but we all care about you, and if you do ever want to share what’s bothering you about this,” he tapped the box with one not-hand, “we’d be more than willing to listen.” Tontu nodded a little, giving an awkward hum of agreement.

“Thank you,” Johanna replied softly, her smile deepening just a little as she looked over the room again, “all of you. That… that really does mean a lot to me.” Her words were just a little choked up, tinged with emotion; she squeezed Hilda again, and the girl felt her own worries fade into the background at the feeling.

Johanna leaned back, into the soft yellow cushions behind her. She closed her eyes, and her sweater shifted with the gentle rise and fall of her chest as she took a deep breath and let it out slowly. Finally, she broke the silence again, her eyes fluttering back open.

“I’ve never really had anyone to tell about this before,” she admitted softly, one hand coming to rest on the box. Her gaze turned down to Hilda, warmth and uncertainty mingling in her eyes. “I did think about showing you, when you were old enough, and…” she let out a gentle sigh. “I suppose now you are. If you want, you can have a look,” her gaze turned back up, over Alfur and Tontu, “all of you.”

“You’re really sure?” Tontu asked, gingerly slipping between the couch and the table, right by her legs. She looked down at him for a moment, then nodded.

“Yes,” she insisted softly, “yes I am.” Carefully she pushed the box into Hilda’s reach, inviting her to take a look. Hilda couldn’t help swallowing as she reached down, her stomach lurching inside as her fingers closed around the lid. It meant a lot that her mum was trusting her with this, that she was being let into this big secret, but that sent her nerves spiking as she gingerly pulled it open.

Inside, the yellow light from above shone off dark plastic and white card; a jumbled pile of Polaroid photographs filled the box, covered by a thin sheen of blue-grey dust. Hilda gingerly picked up the first one, brushing it clean and holding it up to the light to see the washed-out detail.

It was an old family photo; three people, two adults and a child who could only have been their son, stared out from behind the plastic cover, standing together in front of a narrow Trolberg townhouse. Hilda looked over each of them in turn, scrambling to find whatever about this was so important to her mum.

The father was a tall, stern-looking man, with a pale, narrow face and curly reddish-brown hair; he wore a crisp Safety Patrol uniform in the old purple colour, and round silver glasses perched on top of a strangely familiar nose. He was smiling, but his mouth was drawn thin and it didn’t reach his eyes.

Beside him, his partner was a shorter, round-faced woman in a white floral shirt. Her neatly-brushed hair was darker than his, her eyes a little kinder, but there was still something restrained about her expression. Her hands were clasped together in front of her knees, hidden by a long dark blue skirt.

Hilda couldn’t escape the feeling that there was something familiar about their child. He looked slightly younger than her, a little shorter, with his mother’s darker hair and the curve of his father’s nose and a face shape that was somewhere in between. A small smile crossed his face, but even through the faded plastic Hilda could see discomfort in his awkward stance; it distinctly reminded her of David, of that sort of unhappy uncertainty in himself that rose up whenever his fears got too much.

She set the image back down carefully, putting it on the table by the box so that Alfur could have a look, and picked up another. This one was just the boy, standing in front of a small wooden hall. The yellow and brown uniform he wore was unmistakeable, his sash decorated with almost as many badges as Frida’s. But he didn’t look proud; if anything he seemed even more uncomfortable, and something twinged deep down in Hilda’s gut at his expression.

The next photo was better; the same kid with three others, sandwiched happily between two of them and smiling broadly. He seemed more himself, his arms tightly around his friends’ shoulders, and something about the image just felt warmer and happier than the others. But what Hilda really noticed were the uniforms.

The boy was still in his Sparrow Scout attire, now crumpled and stained from playing outside. But the other three, two girls and a boy, were all wearing pale blue tops with a symbol stitched on that looked like a triangular tent. Looking down, Hilda’s gaze fell on the bottom of the frame, where scribbled pencil declared: ‘Ochoco Camporee, Sparrow Scout Expedition Camp, ‘77’

Hilda couldn’t escape the creeping feeling that she was intruding as she put that one down. She felt like she was picking apart someone else’s life, her insides squirming a little as she reached for the next one. But she reminded herself that her mum wanted her to see these, that getting all of this out was important to her, and pressed on.

The rest of the photos were more of the same; it was always either the child, or the whole family, without even another sign of friends. And as they went on and the son got older and older, the smiles got more and more and forced. It was like watching a whole childhood play out in a moment, discomfort turning to sadness turning to what looked almost like resentment. As a teenager the son seemed to give up smiling entirely, keeping his gaze down and straying as far from his parents as they seemed to let him.

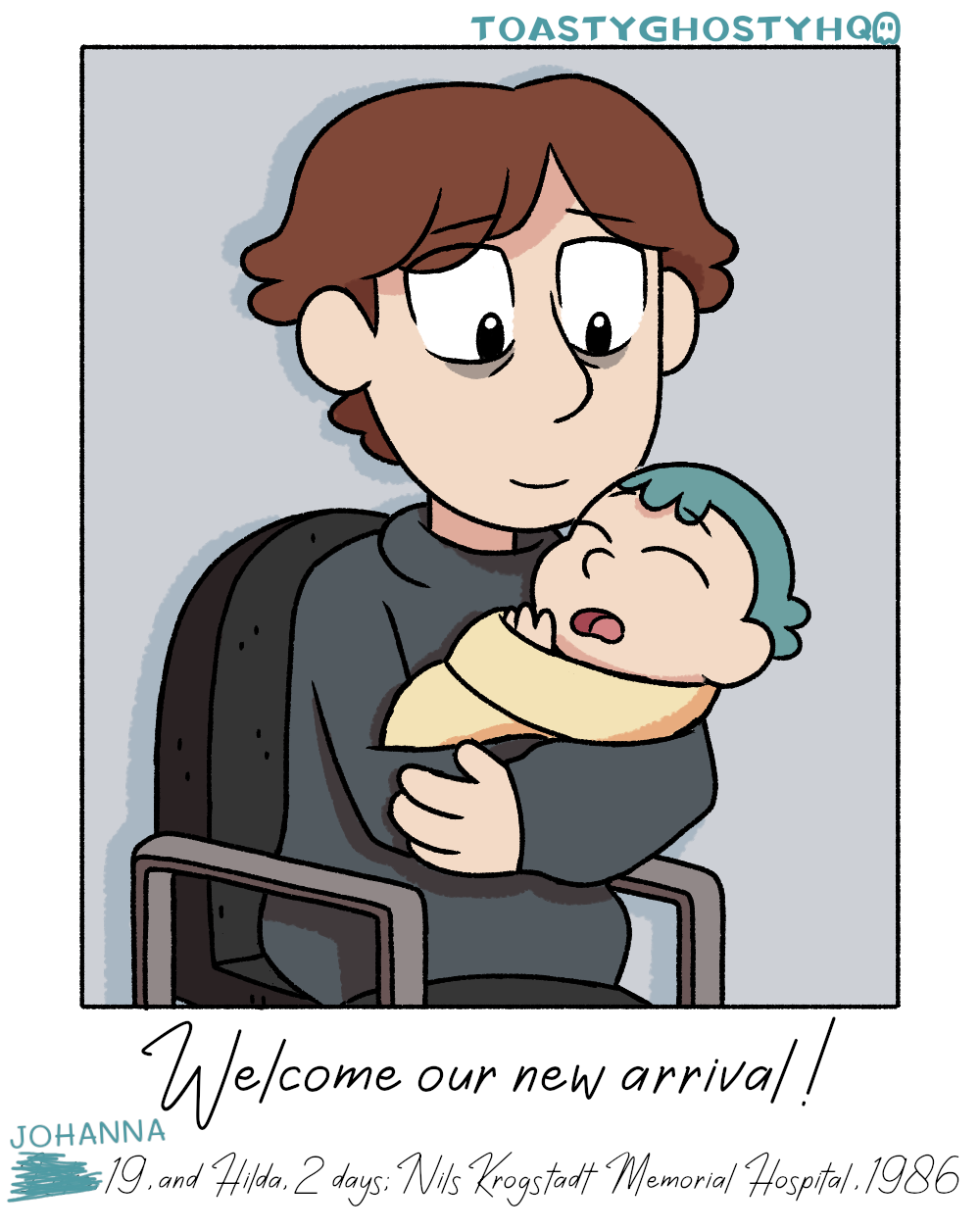

But the last one was different. It wasn’t a strained family picture, punctuated by forced expressions and bad feelings; it was just the son, now definitely an adult, half-curled up in an oversized sweater on a hard-backed hospital chair. His face was lined with exhaustion, grey bags hanging under his eyes, but his expression was alive with warmth and unconditional love, his gaze down on a tiny bundle in his arms.

Hilda couldn’t help gasping as she looked down. He was cradling a baby, so small and so fragile, with delicate reverence. Their skin was flushed, their tiny face scrunched up, and they were swaddled in off-white hospital cloths. But none of that was what really gave her pause; Hilda’s heart near-stopped as she peered at the child, everything slamming to a halt at once, because the baby’s thin hair was a deeply familiar shade of pale blue.

That couldn’t be her, could it? She quickly scanned the picture, hoping this one would have a label like the one from the Camporee, but there was nothing around the weathered borders of the thing. In desperation she flipped it, and finally, there, found what she was looking for; cursive was scrawled out across the back in splotchy black ink, barely readable after all the years:

Welcome our new arrival! it declared. Luke, 19, and Hilda, 2 days; Nils Krogstad Memorial Hospital, Trolberg, 1986.

Hilda flipped the thing back, her stomach doing flips as she looked over the photo again. Because if that was her, if this almost-familiar family was really hers, then who was that cradling her? And suddenly, with a jolt that she couldn’t suppress, everything fell into place.

Because she suddenly knew why she recognised that face. It was a little thinner, marred by exhaustion and not framed by the long brown curls she knew, but it was undeniably the same soft features, same bright, attentive eyes, and same unconditional love and affection and warmth that she knew and loved so much.

“Mum?” She hadn’t realised how heavy the silence was until she broke it, her voice quiet and uncertain. Johanna looked up, eyes widening just a little at the photo in her daughter’s hands. Hilda forced the rest out. “Is that… are these all you?”

One of her mum’s hands reached out, gently closing around Hilda’s own. “Yes, sweetheart,” she said softly, her voice a gentle whisper. “Those are all the photos I have of me from before…” she trailed off, momentarily grasping for the right words. “Before we moved away from my parents.”

“So,” Alfur spoke up, curiosity in his voice, “you were raised as a boy?” Johanna let out a long sigh, shifting uncomfortably. “Not to say that you are a boy, or a man, of course,” he added quickly, “this is all just very new to me.”

“I understand, Alfur,” Johanna soothed calmly, giving a quiet nod. “And yes, I was; it’s called being transgender. When I was born, my Mum and Dad,” she turned back to Hilda, gently squeezing her hand, “your grandparents, thought they had a son.” She tensed at the memories, a shudder in her breaths, and Hilda felt a pang of sympathy at the sight.

Her mum went on, softly. “When I was very little, I didn’t really notice, but by the time I was your age it just felt…” a sigh swallowed her words. “wrong. People calling me a boy just made this horrible, uncomfortable feeling grow in my chest, and I started wishing that I was a girl instead.”

“But you were a girl, really,” Hilda noted softly; her hand slipped from the side of the old photograph, gently closing around her mum’s, “weren’t you?” The woman nodded again, eyes closing for a moment as she thought back.

“I hadn’t realised that then,” she explained; her tone was neutral, just a little strained by buried emotion, but something almost fond crept into it as she continued. “Things changed when I went on that camping trip,” she gestured down to the photo of her with the other kids, the one warm spot in her cold childhood.

“There was another camp near ours, and I made friends with some of the kids there; they said I should just try calling myself a girl, using she and her and all of that.” Her eyes turned just a little misty; she blinked, and for one long moment Hilda was scared she was going to cry. “That summer was the first time I could really be myself.”

“And your parents weren’t happy about that?” Tontu cut in, almost incredulous, like he didn’t want to believe her family would have been so cruel. But Johanna just shook her head sadly, wiping her eyes with her free hand, and Hilda felt her insides squirm again at the pain in her mum’s voice.

“They wanted a son,” she said softly, “not a daughter.” Hilda squeezed her hand, hoping to offer at least some comfort, but she didn’t seem to notice. “No matter what I did, they just forced me to still act like the child they wanted, and not the one they had. Grandpa was better, but I didn’t see him often because he lived so far away.”

“So what did you do?” Hilda asked desperately, her own voice cracking a little with worry. For a moment her mum just didn’t reply, staring off towards the far window, before finally she explained.

“I moved away,” she admitted sadly, looking down at Hilda again; her eyes were wet, shining in the warm light of the room, “as soon as I could, and you came with me. You were probably too young to remember, but for the first few months we had a little flat by the wall, overlooking the railway line. And then your great-grandfather passed away, and he left me the old house in the wilderness.”

“That’s…” for a moment Hilda scrambled for the right words; she wanted to make her mum feel better, to drive back all those awful feelings like the woman so often did for her, but all she could think of was one final question.

“That’s why I’ve never met my grandparents,” she whispered, “isn’t it? Because they never accepted you.” Her mum nodded slowly and sadly, blinking back the tears that kept threatening to spill from her eyes.

“I’m sorry, sweetheart,” she said quietly, looking down. “That’s why I didn’t want you to know; it’s not something I ever want you to have to worry about. It’s not your fault, and there’s nothing you could have done to change it.” And at that, something snapped deep down inside Hilda’s heart; because amidst the pain and sadness in Johanna’s voice, she was sure she also heard guilt.

“It’s not your fault either!” was out before she could stop it. She pulled her hand from her mum’s grip, leaning over and throwing both arms tightly around the woman’s middle instead. “Mum,” she said quickly, her own eyes starting to sting from the weight of everything, “I’m so sorry your parents weren’t… like you.”

She felt her mum tense up at that, but she went on, burying her face in her side. “You’re the best mum I could’ve asked for; you’re a nice, amazing woman, and, and if your Mum and Dad can’t see that, then they don’t deserve to be called that.” Gently, Johanna’s arms closed around her, squeezing her reassuringly. “I’m glad I’ve never met them.”

“Me too,” Alfur added sagely, not-hands clasped behind his back. “I know it’s never easy to cut family out of your life, but honestly, I think you did the right thing,” he explained gently. “I’m sorry your parents didn’t accept your identity, I really am. And I’m sorry if we’ve made you relive any of that pain.”

“Oh,” Johanna sighed fondly, the word choked-up by emotion. She gently pulled Hilda in, up on to her lap, swaddling her in crimson warmth. “What would I do without you?” she asked, sniffling as she held her daughter close and met the elf’s caring gaze.

And for a moment, they just stayed like that, Hilda and her mother in a close embrace, sharing warmth and comfort, while the rest of their little family hung around, offering their own quiet reassurance. Hilda couldn’t help feeling content, listening to the gentle beat of her mother’s heart and basking in the growing warmth, when suddenly the silence was awkwardly broken.

“Hey, mom?” Tontu questioned, his head tilting back so that his noise pointed up at Johanna’s face. “Can I, uh, ask you something?” She gave a smile back, small but warm, despite the twinge of hesitance in her answer.

“Of course you can, Tontu,” she replied softly. He shifted, looking down at the photos now spilling across the table, then back up.

“How come you’re still keeping those around?” he asked, blunt but not unkindly. Hilda felt her mum tense up all over again, and he seemed to notice too, more words spilling out from behind his fur. “I mean, they’re only making you feel bad; it seems almost like you were happier when you thought they were lost. So why not throw them out?”

Johanna sighed, her whole body shifting with the long breath. “They’re family photos,” she breathed quietly, her face falling as the warmth around her ebbed again. “I know it might be… different for nisse, but we can’t just get rid of stuff like that.”

“Why not?” he pressed, head tilting over in confusion. Johanna frowned, mixed feelings brewing in her eyes; at the sight, Hilda found herself scrambling for something to say, desperate to reignite the fading warmth in the air.

“Because…” for a moment Johanna seemed lost in thought, that same expression from when she had first found the box settling back on her face. “Because they’re important.” She gestured weakly to the Polaroids. “I know I don’t like to remember it, but that’s still who I was, and those are still my parents.” And finally, Hilda found the words.

“So?” she burst out, determination filling her chest. “They were awful to you, and they tried to make you into someone you weren’t.” She couldn’t help a sigh of her own. “Mum, you don’t need to remind yourself of that; photos are meant to be for remembering good things!” Her mum opened her mouth to reply, but another voice cut her off.

“I’m afraid she’s right,” Alfur put in; his gaze was down, looking over the cold and miserable images. “There’s a difference, I think, between forgetting something and choosing not to remember it.”

He went on calmly, pacing along the table. “You can’t make those bad memories go away, but if you ask me, it’s not fair to yourself to keep reliving them either.” There was something almost bitter in his words, disguised venom for the people who had hurt Johanna so deeply, and it resonated deep inside her daughter’s core

“Exactly!” Hilda picked up again, shifting back in her mum’s arms to meet the woman’s gaze. “Your Mum and Dad don’t get to tell you who you are, or how you live your life,” she insisted, words spilling out in a torrent, “so why should they get to say what you keep?”

And at that, Johanna seemed to break just a little. She let out a shaky breath, falling back against the couch cushions, and for one long moment Hilda was terrified that she’d said the wrong thing. But then that small, hurt smile returned to her mum’s face, embers of warmth reigniting in her watery eyes, and the girl felt her insides settle as she spoke softly in reply.

“They shouldn’t,” she breathed, almost like she didn’t, couldn’t believe it. She shifted forwards again, blinking back a few stray tears as she looked over the images. “I always thought that I had to keep these,” she explained, one hand idly reaching down; the other still held Hilda close, “that I somehow still owed Mum and Dad that, at least.

“I was actually…” she trailed off, strangling a sob in her throat, “happy, when I lost them. I thought then I could just move on, and it wouldn’t be my fault.” She squeezed her daughter tightly, emotions flowing free. “But you’re right, all of you; they’re just bad memories.”

Her hand drifted away from the table, over to where Tontu was standing, and gently she ruffled the fur on the back of his head. “So thank you.”

“Does that mean we’re getting rid of them?” Hilda couldn’t help asking, her smile broadening into almost a grin. Her mum paused for a moment, head tilted just a little, before she smiled in kind and nodded with newfound determination.

“Most of them,” she admitted; her grip around Hilda loosened, her hand stretching out to gather up what she wanted. The girl watched as she picked out two from the pile; the photo of her with her friends from camp, and the one Hilda had last held, the one of her as a newborn, safe and loved in her mother’s arms just like she was now.

“I want to keep these two,” Johanna explained gently, holding them up to the light with a broadening smile. “But, now, because of you three, I know I don’t need the others anymore.” Nobody disagreed with that.

“Hey, mum?”

“Yes, sweetheart?” Johanna looked up from her drawing desk; her daughter was standing just off to the side, right by the edge of the sofa, and she couldn’t help feeling a surge of fondness at the sight. Hilda had a familiar smile on her face, her body leaning slightly to one side, and her arms clasped behind her back; instinctively the woman got the sense that she had something planned.

She hesitated for a moment, taking a brisk breath, then stepped forwards. “I’ve got something for you,” she explained quickly, shifting her weight over her feet. “Last night got me thinking, so…” she trailed off, taking a deep breath, and for a moment Johanna felt a spike of concern. “Here.”

Her hands moved out from behind her back, holding out a small, square shape for Johanna to see. Immediately she recognised it, and with that came a surge of confusion. Because it was one of the photos from the previous evening, the one with her cradling Hilda for the first time as a tiny, frail newborn. Carefully she took it, not sure what Hilda wanted her to see.

“Turn it over?” the girl encouraged, a hint of uncertainty in her voice. Johanna paused, something deep in her gut twinging at the idea; she knew what was on there already. Her family had long made a point of marking every photo with names, dates, and locations, and she knew uncomfortably well what they’d left on the back of every one of her.

But she also trusted her daughter, and after everything that had happened last night, that trust won out. So she carefully flipped the photo, squinting down at the old writing, only to freeze at the sight. Most of it was still the same, her mother’s handwriting in familiar black biro, but one word had been changed. Four letters had been scratched out, scribbled over so thoroughly that they were unreadable, and in their place, in the pale blue pen that Johanna knew her daughter reserved for her most important sketches and wilderness notes, was a new name:

JOHANNA, 19, and Hilda, 2 days; Nils Krogstad Memorial Hospital, Trolberg, 1986.

“I just thought it should have your real name,” Hilda broke the silence; Johanna felt her heart break a little at the uncertainty in the girl’s tone, “instead of the one your parents gave you?”

And at that, Johanna felt something give way inside. All of those soft feelings from last night; the warmth of a loving family, the lightness of a long-carried burden being shrugged loose, and that beautiful freeing feeling of being accepted; surged at once. She barely had time to set the photo down before it all welled up, her eyes stinging with happy tears.

“Oh, Hilda,” she breathed, stepping down from her chair and opening her arms. “Come here?” Hilda beamed in reply, falling happily into the offered embrace. Her mum just squeezed her tightly, feeling the last of the pain of the past melt away into the background. Because none of it mattered anymore; what mattered was that she was free of her parents, that she had a daughter and a family who loved her for who she was, and that was enough.

“I love you,” she whispered softly, feeling Hilda’s arms reach up to return the hug.

“I love you too, mum.”